Alaska class cruiser

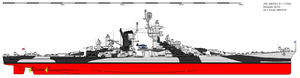

A detailed outboard profile of the Alaska class design. |

|

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Alaska class |

| Builders: | New York Shipbuilding Corporation[1][2][3] |

| Operators: | United States Navy |

| In commission: | 17 June 1944 – 17 February 1947 |

| Planned: | 6 |

| Completed: | 2 |

| Cancelled: | 4[A 1] |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Large cruiser[A 2] |

| Displacement: |

29,771 tons |

| Length: | 808 ft 6 in (246.43 m) overall[4] |

| Beam: | 91 ft 9.375 in (28.0 m)[4] |

| Draft: |

27 ft 1 in (8.26 m) (mean)[1] 31 ft 9.25 in (9.68 m) (maximum)[4] |

| Propulsion: | 4-shaft General Electric steam turbines, double-reduction gearing,[5] 8 Babcock & Wilcox boilers[6] 150,000 shp (112 MW)[4] |

| Speed: | 31.4[2]–33 knots[6][7][8] (36.1–38 mph) |

| Range: | 12,000 nautical miles (22,000 km) at 15 knots (28 km/h)[4] |

| Complement: | 1,517[6][8]–1,799[9]–2,251[1][2][A 3] |

| Armament: |

Nine 12-inch (305 mm)/50 caliber Mark 8 guns[4] (3×3) |

| Armor: |

Main side belt: 9" gradually thinning to 5"[6] |

| Aircraft carried: | 4× OS2U Kingfisher or SC Seahawk[10][A 4] |

| Aviation facilities: | Enclosed hangar located amidships[6][11] |

The Alaska class cruisers were a class of six very large cruisers ordered prior to World War II for the United States Navy. Although often called battlecruisers, officially the Navy classed them as Large Cruisers (CB). Their intermediate status is reflected in their names relative to typical U.S. battleship and cruiser naming practices,[A 5] all were named after "territories or insular areas" of the United States.[A 6] Of the six that were planned, only three were laid down; two were completed, and the third's construction was suspended on 16 April 1945 when she was 84% complete. The finished two, Alaska and Guam, served with the U.S. Navy for the last two years of World War II as bombardment ships and fast carrier escorts. They were both decommissioned in 1947 after spending only 32 and 29 months in service, respectively.

The idea for a large cruiser class originated in the early 1930s, when the U.S. Navy wanted a counter to the "pocket battleships" (Deutschland class) that were being launched and commissioned by Germany. Though nothing resulted immediately, planning for ships that eventually evolved into the Alaska class began in the later 1930s after the deployment of Germany's Scharnhorst class and rumors that Japan was constructing a new battlecruiser class.[7][A 7] The Alaska class were intended to serve as "cruiser-killers", capable of seeking out and destroying these post-Treaty heavy cruisers. To facilitate their purpose, the class was given large guns of a new and expensive design, limited armor protection against 12-inch shells, and machinery capable of speeds of about 31–33 knots (36–38 mph, 58–61 km/h).

Contents |

Background

Heavy cruiser development was steadied between World War I and World War II by the terms of the Washington Naval Treaty and successor treaties and conferences. In this treaty, the United States, Britain, Japan, France, and Italy had agreed to limit heavy cruisers to 10,000 tons displacement with 8-inch main armament. Up until the Alaska class, U.S. cruisers designed between the wars followed this pattern.[12]

The initial impetus for the design of the Alaska class came from the deployments of the so-called pocket battleships in the early 1930s. Though no actions were taken immediately, plans were revived in the late 1930s when intelligence reports indicated Japan was planning or building "super cruisers" which were much more powerful than U.S. heavy cruisers.[3][6][11][13][A 8] The Navy responded in 1938, when a request from the General Board was sent to the Bureau of Construction and Repair for a "comprehensive study of all types of naval vessels for consideration for a new and expanded building program".[14] The U.S. President at the time, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, may have taken a lead role in the development of the class with his desire to have a counter to raiding abilities of Japanese cruisers and German pocket battleships,[15] which had led to them being called "politically motivated",[16] but these claims are difficult to verify.[6][17]

Design

One historian described the design process of the Alaska class as "torturous" due to the numerous changes and modifications made to the ships' layouts by numerous departments and individuals.[7] Indeed, plans resulted in at least nine different layouts,[18] ranging from 6,000-ton Atlanta-class antiaircraft cruisers[19] to "overgrown" heavy cruisers[7] and a 38,000-ton mini-battleship that would have been armed with twelve 12-inch and sixteen 5-inch guns.[19] The General Board, in an attempt to keep the displacement under 25,000 tons, allowed the designs to offer only limited underwater protection. As a result, the Alaska class, when built, were vulnerable to torpedoes and shells that fell short of the ship.[20] The final design chosen was a scaled-up Baltimore class that had the same machinery as the Essex-class aircraft carriers. This ship combined a main armament of nine 12-inch guns with protection against 10-inch gunfire into a hull that was capable of 33 knots.[13]

The new class was officially ordered in September 1940 along with a plethora of other ships as a part of the Two-Ocean Navy Act.[11][21][A 9] The new ships' role had been altered slightly; in addition to their surface-to-surface role, they were planned to protect carrier groups. Because of their bigger guns, greater size and increased speed, they would be more valuable in this role than heavy cruisers, and they would also provide insurance against reports that Japan was building super cruisers more powerful than U.S. heavy cruisers.[11]

Possible conversion to aircraft carriers

_launching.jpg)

Yet another drastic change was considered during the "carrier panic" of early 1942. At this point, with Saratoga out until at least May for repairs after torpedo damage and Lexington lost in the Battle of the Coral Sea, the Navy and the President realized that the United States needed more aircraft carriers as quickly as possible. As a result, the Bureau of Ships decided to convert a few hulls that were currently under construction to carriers. At different times during 1942, they considered converting parts or all of the Cleveland-class light cruisers, the Baltimore-class heavy cruisers, the Alaska class, or even one of the Iowa-class battleships; in the end, they chose the Clevelands.[22]

A conversion of the Alaska cruisers to carriers was "particularly attractive"[22] because of the many similarities between the design of the Essex-class aircraft carriers and the Alaska class, including the same machinery.[23] However, when Alaska cruisers were compared to the Essex carriers, converted cruisers would have had a shorter flight deck (so they could have carried only 90% of the aircraft),[22] would have been 11 feet lower in the water, and could travel 8,000 miles fewer at 15 knots (17 mph). In addition, the large cruiser design did not include the massive underwater protections found in normal carriers due to the armor weight devoted to counter shell fire. Lastly, an Alaska conversion could not satisfy the Navy's goal of having new aircraft carriers quickly, as the work needed to modify the ships into carriers would entail long delays. With these in mind, all planning involved with converting the Alaskas was ended on 7 January 1942.[24]

Construction

Of the six Alaska-class cruisers that were planned, only three were laid down. The first two, Alaska and Guam, were completed. Construction on Hawaii, the third, was suspended on 16 April 1947 when she was 84% complete.[3][14] The last three, Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Samoa, were delayed since all available materials and slipways were allocated to higher priority ships, such as aircraft carriers, destroyers, and submarines. Construction had still not begun when steel shortages[25] and a realization that these "cruiser-killers" had no more cruisers to hunt—as the fleets of Japanese cruisers had already been defeated by aircraft and submarines—made the ships "white elephants".[6] As a result, construction of the last three members of the class never began, and they were officially canceled on 24 June 1943.[26][27][28]

Service history

Alaska and Guam served with the U.S. Navy in the last years of World War II. Similar to the Iowa-class fast battleships, their speed made them useful as shore bombardment ships and fast carrier escorts. Both protected Franklin when she was on her way to be repaired in Guam after being hit by two Japanese bombs. Afterward, Alaska supported the landings on Okinawa, while Guam went to San Pedro Bay to become the leader of a new task force, Cruiser Task Force 95. Guam, joined by Alaska, four light cruisers, and nine destroyers, led the task force into the East China and Yellow Seas to conduct raids upon shipping. However, they only encountered Chinese junks.[1][2] By the end of the war, the two had become celebrated within the fleet as excellent carrier escorts.[8]

After the war, both ships were decommissioned and "mothballed" in 1947[1][2] after having spent 32 and 29 months in service, respectively.[19] In 1958, the Bureau of Ships prepared two feasibility studies to explore whether Alaska and Guam could be suitably converted into guided-missile cruisers. The first study involved removing all of the guns in favor of four different missile systems. At $160 million, this proposed removal was seen as cost-prohibitive, so a second study was initiated. The study left the forward batteries (the two 12-inch triple turrets and three of the 5-inch dual turrets) unchanged, and added a reduced version of the first plan on the stern of the ship. Even though the proposals would have cost approximately half as much as the first study's plan ($82 million), it was still seen as too expensive.[29] As a result, both ships were stricken from the Naval Vessel Register on 1 June 1960. Alaska was sold for scrap on 30 June 1960, and Guam on 24 May 1961.[1][2]

The still-incomplete Hawaii was considered for a conversion to be the Navy's first guided-missile cruiser for a time;[A 10] this thought lasted until 26 February 1952, when a different conversion to a "large command ship" was contemplated. In anticipation of the conversion, her classification was changed to CBC-1. This would have made her a "larger sister" for Northampton,[6] but a year and a half later (9 October 1954) she was re-designated CB-3. Hawaii was stricken from the Naval Vessel Register on 9 June 1958 and was sold for scrap in 1959.[3]

"Large cruisers" or "battlecruisers"?

_and_USS_Alaska_(CB-1)_at_Norfolk,_Virginia,_1944.jpg)

Early in its development, the class used the designation CC, which signified that they were to be battlecruisers in the tradition of the Lexington class;[A 11] however, the designation was later changed to CB to reflect their new name, "large cruiser", and the practice of referring to them as battlecruisers was officially discouraged.[17] The U.S. Navy then named the individual vessels after U.S. territories, rather than states (as was the tradition with battleships) or cities (for which cruisers were named), to symbolize the belief that these ships were supposed to play an intermediate role between heavy cruisers and fully-fledged battlecruisers.[7]

They resembled contemporary battleships in appearance, weighed only 5,000 tons less in displacement, mounted the familiar 2-A-1 main battery,[A 12] shared a similar massive columnar mast, and carried 5"/38 caliber dual-purpose guns along the sides of the superstructure, although the battleships carried eight (older refitted ships) or ten (post-South Dakota) 5"/38 twin mounts flanking the superstructure while the Alaska cruisers only carried six: one at each of the four superstructure corners, and one each at fore and aft on the centerline.[30][31]

There are two main arguments for referring to the Alaska class as "large cruisers". The first is their armor; while they were able to withstand more fire from guns than any other cruiser afloat, they were virtually defenseless against torpedoes because they had no sub-divisions within the hull and no anti-torpedo scheme. The lack of underwater protection would also make them vulnerable to shells which fell slightly short of their mark and continued underwater to hit the hull.[7] In addition, their armor was only marginally capable of stopping 12" fire;[32] they were vulnerable to battleship fire (14–16" fire) at any range.[33] The second argument lies entirely in their design. The design of the Alaska class ships was, from the keel up, just a scaled-up treaty cruiser finally unencumbered by the Washington, London and Second London naval treaties.[6] In addition, despite being much larger than the Baltimore class, the secondary battery of the "large cruisers" was only slightly larger. Whereas the Alaska class carried twelve 5"/38 caliber, fifty-six 40 mm, and thirty-four 20 mm guns, the Baltimore class carried the same number of 5"/38s, eight fewer 40 mm, and only ten fewer 20 mm.[6] In addition to all of this, author Richard Worth remarked that when they were finally completed, launched, and commissioned, they had the "size of a battleship but the capabilities of a cruiser".[7]

Despite these cruiser-like characteristics, and the U.S. Navy's insistence on their status as cruisers, the Alaska class were frequently described as battlecruisers at the time.[34] Some modern historians take the view that this is a more accurate designation because they believe that the ships were "in all sense of the word, battlecruisers", with all the vulnerabilities of the type.[9] The traditional Anglo-American battlecruiser concept had always sacrificed protection for the sake of speed and armament, meaning they were not intended to stand up against the guns they themselves carried.[33][35] The Alaska's percentage of armor tonnage, 28.4%, was slightly less than that of battlecruisers and fast battleships; the British King George V class, the battlecruiser HMS Hood, and the American Iowa class all had armor percentages between 32 and 33%. In fact, older battlecruisers, such as the Invincible (19.9%), had a significantly lower percentage.[36] In terms of displacement, the Alaska class was about twice as heavy as the newest heavy cruisers (the Baltimore class).[34] In addition, they had much larger guns; while the Alaska class carried nine 12"/50 caliber guns that were as good as, if not superior to, the old 14"/50 caliber gun used on the U.S. Navy's pre-treaty battleships,[37] the Baltimore class had an equal number of 8"/55 caliber Marks 12 and 15 guns.[38]

Armament

Main battery

_firing_main_battery,_1944-45.jpg)

As built, the Alaska class had nine 12"/50 caliber Mark 8 guns mounted in three triple (3-gun) turrets,[37] with two turrets forward and one aft, a configuration known as "2-A-1". The previous 12" gun manufactured for the U.S. Navy was the Mark 7 version, which had been designed and installed in the 1912 Wyoming-class battleships. The Mark 8 was of considerably higher quality; in fact, it "was by far the most powerful weapon of its caliber ever placed in service."[39] Designed in 1939, it weighed 121,856 pounds (55,273 kg), including the breech, and could sustain an average rate of fire of 2.4–3 rounds a minute. It could throw a 1,140 lb. (517.093 kg) Mark 18 armor piercing shell 38,573 yards (35,271 meters) at an elevation of 45°, while the guns had a 344-shot "barrel life"[37] (about 54 more than the much larger but similar 16"/50 caliber Mark 7 gun found in the Iowa battleships.).[40]

The turrets were very similar to those of the Iowa-class battleships, but differed in several ways; for example, the Alaska-class had a two-stage powder hoist, instead of Iowa-class's one-stage hoist. These differences made operating the guns safer and increased the rate of fire. Also, a "projectile rammer" was added to Alaska and Guam. This machine transferred shells from storage on the ship to the rotating ring that fed the guns. However, this feature proved unsatisfactory, and it was not planned for Hawaii or any subsequent ships.[37]

Because Alaska and Guam were the only two ships to mount these guns, only ten turrets were made during the war (three for each ship including Hawaii and one spare). They cost the Navy $1,550,000 each and were the most expensive heavy guns purchased by the U.S. Navy in World War II.[17]

,_1945.jpg)

Secondary battery

The secondary battery of the Alaska class was composed of twelve dual-purpose (anti-air and anti-ship) 5"/38 caliber guns in twin mounts, with four offset on each side of the superstructure (two on each beam) and two centerline turrets fore and aft. The 5"/38 was originally intended for use on only destroyers built in the 1930s, but by 1934 and into World War II it was being installed on almost all of the U.S.'s major warships, including aircraft carriers, battleships, and heavy and light cruisers.[41]

Anti-aircraft battery

For anti-aircraft armament, the Alaska class ships carried 56 x 40 mm guns and 34 x 20 mm guns. These numbers are comparable to 48 x 40 mm and 24 x 20 mm on the smaller Baltimore class heavy cruisers and 80 x 40 mm and 49 x 20 mm on the larger Iowa battleships.[1][42][43]

Arguably the most efficient light anti-aircraft gun of World War II, the 40 mm Bofors was used on nearly every major warship in the U.S. and UK fleets during World War II from about 1943 to 1945. Although they were a descendant of German and Swedish designs, the Bofors mounts used by the United States Navy during World War II had been heavily "Americanized", which brought the guns up to U.S. Navy standards. This new standard resulted in a gun system set to English standards (now known as the Standard System) with interchangeable ammunition, simplifying the logistics situation for World War II. When coupled with hydraulic couple drives to reduce salt contamination and the Mark 51 director for improved accuracy, the 40 mm Bofors became a fearsome adversary, accounting for roughly half of all Japanese aircraft shot down between 1 October 1944 and 1 February 1945.[44]

The Oerlikon 20 mm anti-aircraft gun was one of the most extensively used anti-aircraft guns of World War II; the U.S. alone manufactured a total of 124,735 of these guns. When activated in 1941, they replaced the 0.50" M2 Browning machine gun on a one-for-one basis. The Oerlikon gun remained the primary anti-aircraft weapon of the United States Navy until the introduction of the 40 mm Bofors in 1943.[45]

Ships

- USS Alaska (CB-1) was commissioned on 17 June 1944. She served in the Pacific, screening aircraft carriers, providing shore bombardment at Okinawa, and going on raiding missions in the East China Sea. She was decommissioned on 17 February 1947 after less than three years of service and was scrapped in 1960.[1]

- USS Guam (CB-2) was commissioned on 17 September 1944. She served in the Pacific with Alaska on almost all of the same operations. Along with Alaska, she was decommissioned on 17 February 1947 and was scrapped in 1961.[2]

- USS Hawaii (CB-3) was intended as a third ship of the class, but she was never completed. Numerous plans to utilize her as a guided-missile cruiser or a large command ship in the years after the war were fruitless, and she was scrapped.[3]

- USS Philippines (CB-4) was planned as the fourth ship of the class. She was to be built at Camden, New Jersey, but was canceled before construction could begin.[26]

- USS Puerto Rico (CB-5) was planned as the fifth ship of the class. She was to be built at Camden, New Jersey, but was canceled before construction could begin.[27]

- USS Samoa (CB-6) was planned as the sixth ship of the class. She was to be built at Camden, New Jersey, but was canceled before construction could begin.[28]

Notes

- ↑ Hawaii was laid down but never completed.

- ↑ The class were officially rated as "large cruisers" by the U.S. Navy. However, some modern historians argue that the class should really be classified as battlecruisers. See Worth, 305.

- ↑ Sources vary greatly on just how many people composed the complement of the ship.

- ↑ The Seahawk made its operational debut upon Guam on 22 October 1944.

- ↑ With only a very few exceptions, U.S. battleships were named for states, e.g. USS Nevada (BB-36) or USS New Jersey (BB-62), while cruisers were named for cities, e.g. USS Juneau (CL-52) or USS Quincy (CA-71). See United States ship naming conventions.

- ↑ Alaska and Hawaii were "insular areas" of the United States at the time; they acceded to the Union as the forty-ninth and fiftieth States in 1959.

- ↑ Jane's thought that this mythical battlecruiser, the notional Chichibu class, would have six 12-inch guns and 30-knot (34.52 mph) speed packed into a 15,000-ton ship. See Fitzsimons, Volume 1, 58 and Worth, 305.

- ↑ Japan actually developed plans for two of the super cruisers in 1941, though it was mostly in response to the new Alaska ships. However, the ships were never ordered due to the greater need for carriers.

- ↑ Along with the Alaskas, 210 other ships were ordered at the same time: two Iowa-class battleships, five Montana-class battleships, twelve Essex-class aircraft carriers, four Baltimore-class heavy cruisers, 19 Cleveland-class light cruisers, four Atlanta-class light cruisers, 52 Fletcher-class destroyers, twelve Benson-class destroyers and 73 Gato-class submarines.

- ↑ A similar proposal was made to convert the uncompleted Iowa-class battleship USS Kentucky (BB-66) into the first guided-missile battleship (BBG), but as with the proposal for Hawaii this conversion never materialized, and Kentucky was scrapped in 1958.

- ↑ The Lexington class would have been designated CC-1 through CC-6, had they been built.

- ↑ It was also found on the North Carolina-class battleship, South Dakota-class battleship, Iowa-class battleship and Baltimore-class heavy cruiser.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 "Alaska". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History & Heritage Command. http://hazegray.org/danfs/cruisers/cb1.txt. Retrieved 14 October 2008.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 "Guam". DANFS. http://hazegray.org/danfs/cruisers/cb2.txt. Retrieved 14 October 2008.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 "Hawaii". DANFS. http://hazegray.org/danfs/cruisers/cb3.txt. Retrieved 14 October 2008.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 Dulin, Jr., Garzke, Jr., 184.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Fitzsimons, Bernard, ed., Volume 1, 59.

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 6.12 6.13 6.14 6.15 6.16 Gardiner and Chesneau, 122.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 Worth, 305.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Miller, 200.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Osbourne, 245.

- ↑ Swanborough and Bowers, 148.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Pike, John (2008). "CB-1 Alaska Class". GlobalSecurity.org. http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/systems/ship/cb-1.htm. Retrieved 19 October 2008.

- ↑ Bauer and Roberts, 139.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Scarpaci, 17.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Dulin, Jr., Garzke, Jr., 189.

- ↑ Dulin, Jr. and Garzke, Jr., 24 and 179.

- ↑ Dulin Jr., Garzke, Jr., 267.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Morison and Polmar, 85.

- ↑ Dulin, Jr. and Garzke, Jr., 179–183.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Dulin, Jr. and Garzke, Jr., 179.

- ↑ Dulin, Jr., Garzke, Jr., 183.

- ↑ Rohwer, 40.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Friedman, 190.

- ↑ Fitzsimons, Volume 1, 58.

- ↑ Friedman, 191.

- ↑ Fitzsimons, Volume 1, 59.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 "Philippines". DANFS. http://hazegray.org/danfs/cruisers/cb4.htm. Retrieved 15 October 2008.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 "Puerto Rico". DANFS. http://hazegray.org/danfs/cruisers/cb5.htm. Retrieved 15 October 2008.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 "Samoa". DANFS. http://hazegray.org/danfs/cruisers/cb6.htm. Retrieved 15 October 2008.

- ↑ Dulin, Jr., Garzke Jr., 187.

- ↑ An example of an older refitted ship: "Nevada". DANFS. http://hazegray.org/danfs/battlesh/bb36.htm. Retrieved 19 October 2008.

- ↑ An example of a newer ship: "South Dakota". DANFS. http://hazegray.org/danfs/battlesh/bb57.htm. Retrieved 19 October 2008.

- ↑ Dulin Jr., Garzke Jr. (1976), p. 283

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Dulin Jr., Garzke Jr. (1976), p. 279.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Morison, Morison and Polmar, 84.

- ↑ Sumida, Jon Tetsuro, In Defence of Naval Supremacy. London: Routledge (1993) p.262.

- ↑ Friedman, Battleship Design and Development, 166–173

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 37.3 DiGiulian, Tony (7 February 2008). "12"/50 (30.5 cm) Mark 8". Navweaps.com. http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WNUS_12-50_mk8.htm. Retrieved 15 October 2008.

- ↑ DiGiulian, Tony (7 February 2008). "8"/55 (20.3 cm) Marks 12 and 15". Navweaps.com. http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WNUS_8-55_mk12-15.htm. Retrieved 15 October 2008.

- ↑ Dulin, Jr. and Garzke, Jr., 190.

- ↑ DiGiulian, Tony (7 February 2008). "United States of America 16"/50 (40.6 cm) Mark 7". Navweaps.com. http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WNUS_16-50_mk7.htm. Retrieved 16 October 2008.

- ↑ DiGiulian, Tony (27 March 2008). "United States of America 5"/38 (12.7 cm) Mark 12". Navweaps.com. http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WNUS_5-38_mk12.htm. Retrieved 25 July 2008.

- ↑ "Baltimore". DANFS. http://hazegray.org/danfs/cruisers/ca68.txt. Retrieved 15 October 2008.

- ↑ "Iowa". DANFS. http://hazegray.org/danfs/battlesh/bb61.htm. Retrieved 15 October 2008.

- ↑ DiGiulian, Tony (14 May 2008). "Sweden, British, USA, German and Japanese Bofors 40 mm/56 (1.57") Model 1936". Navweaps.com. http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WNUS_4cm-56_mk12.htm. Retrieved 25 July 2008.

- ↑ DiGiulian, Tony (14 July 2008). "British, Swiss and USA 20 mm/70 (0.79") Oerlikon Marks 1, 2, 3 and 4". Navweaps.com. http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WNUS_2cm-70_mk234.htm. Retrieved 25 July 2008.

Bibliography

- Bauer, Karl Jack; Roberts, Stephen S. (1991). Register of Ships of the U.S. Navy, 1775–1990: Major Combatants. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0313-2-6202-0. (Google books link)

- Dulin, Jr.,Robert O.; Garzke, Jr.; William H. (1976). Battleships: United States Battleships in World War II. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1557-5-0174-2. (Google Books link)

- Fitzsimons, Bernard, ed. (1978). Illustrated Encyclopedia of 20th Century Weapons and Warfare. Volume 1. London: Phoebus.

- Friedman, Norman (1983). U.S. Aircraft Carriers: An Illustrated Design History. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0870-2-1739-9. (Google Books link)

- Gardiner, Robert; Chesneau, Roger (1980). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships, 1922–1946. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0870-2-1913-8. (Google Books link)

- Miller, David (2001). Illustrated Directory of Warships of the World: From 1860 to the Present. Osceola: MBI Publishing Company. ISBN 0760311277. OCLC 48527933. (Google books link)

- Morison, Samuel Loring; Polmar, Norman (2003). The American Battleship. Zenith Imprint. ISBN 0760-3-0989-2. (Google Books link)

- Osborne, Eric W. (2004). Cruisers and Battle Cruisers: An Illustrated History of Their Impact. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1851-0-9369-9. (Google Books link)

- Rohwer, Jürgen (1992). Chronology of the War at Sea, 1939–1945: The Naval History of World War Two. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1591-1-4119-2. (Google books link)

- Scarpaci, Wayne (April 2008). Iowa Class Battleships and Alaska Class Large Cruisers Conversion Projects 1942–1964: An Illustrated Technical Reference. Nimble Books LLC. ISBN 1934840386. (Google Books link)

- Swanborough, Gordon; Bowers, Peter M. (1968). United States Navy Aircraft Since 1911. Funk & Wagnalls.

- Tucker, Spencer C.; Roberts, Priscilla Mary; Greene, Jack; Kingseed, Cole C.; Muir, Malcolm; Zabecki, David T. (DRT); Millett, Allan R. (FRW) (1976). World War II: A Student Encyclopedia. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1557-5-0174-2. (Google Books link)

- Worth, Richard (2002). Fleets of World War II. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0306-8-1116-2. (Google Books link)

External links

Media related to Alaska class cruiser at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Alaska class cruiser at Wikimedia Commons- The Genesis of the Alaska Class Large Cruisers: Part One

- Photographs of the Alaska class

- Alaska class Large Cruisers From U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence recognition manual ONI 200, Issued 1 July 1950

|

|||||

|

||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||